In part two of our three-part series on microplastics, we take a look at how we are tracking their spread and efforts to stem the tide. Part one described our current understanding of the problem. Our final installment will look at hopeful solutions.

Many organizations are casting a wide net to grapple with the growing microplastics problem (see our previous post “Where Our Understanding Lies”). Many types of organizations, trade groups, consultants, and government agencies are keeping tabs on plastic production and proliferation. Their missions vary somewhat, but their overarching goals are to understand and lessen the impacts on people and the planet.

The Global Partnership on Plastic Pollution and Marine Litter (GPML) represents groups worldwide trying to slow the proliferation of plastic pollution. The partnership operates under the auspices of the UN Environment Programme (UNEP). In 2023, GPML published “Turning Off the Tap,” a report that covers the causes of pollution, not just the symptoms. It also advocates for change.

Because stemming the production and uses of plastics has economic repercussions, GPML calls for a “systems change scenario” that combines reducing the spread of plastic waste while transforming the market to a more circular model. That sentiment is echoed by The Pew Charitable Trust’s review of the state of plastic in the 2020 report “Breaking the Plastic Wave,” produced with SYSTEMIQ, a company collaborating on projects for environmental system change.

System change scenarios are just as they sound: creating multiple pathways to pivot away from business as usual. For plastic, they include:

- Increased recycling

- Investing in biodegradable products

- Reducing unnecessary packaging

- Developing ways to covert plastics to other uses

- Curbing the international waste trade

- Finding substitutes with fewer downsides

Those changes require shifts in thinking, by investors, manufacturers, and consumers. Progress will require moving from primarily a linear economy of single-use plastic to multiple pathways of elimination, reduction, and innovative reuses. Many actors will need to make commitments for success.

Work has started to build global buy-in for change. In a historic decision in March 2022, all 193 UN Member States voted at the fifth UN Environment Assembly to end plastic pollution. This year, critical negotiations about the future of plastic pollution are in motion. A primary objective is to form a legally binding global agreement by the end of 2024 to stop plastic pollution.

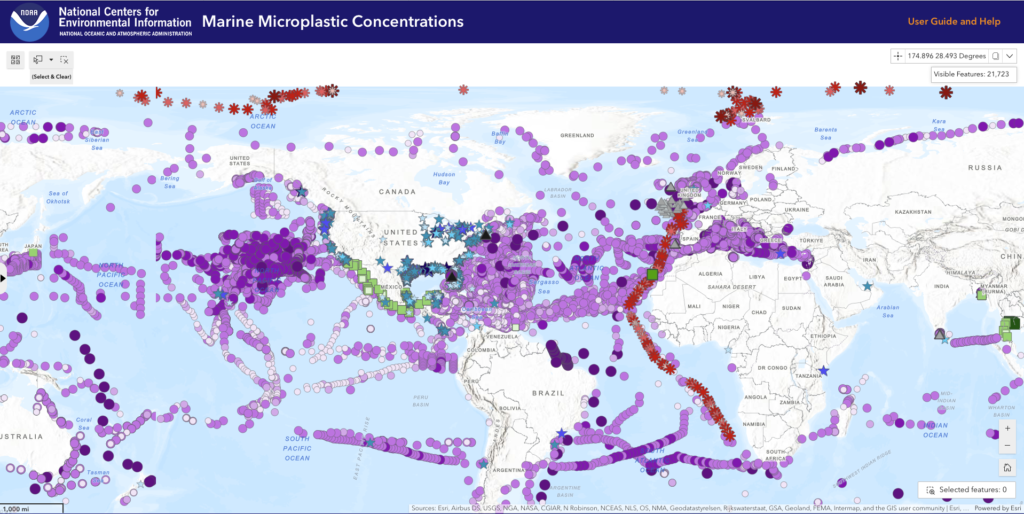

A hinderance remains a lack of data about plastic production, migration, and disposal. One stopgap that has emerged recently may help. NOAA’s Marine Microplastics Database is one of the newest databases for sharing knowledge about microplastic pollution in water around the world. A user application provides data on the occurrence, distribution, and quality of global microplastics and is the repository of multiple datasets from bodies of water near every continent. NOAA’s map of microplastic concentrations gives new meaning to “seeing is believing.”

In our last post in this series, we’ll focus on how necessity fuels invention, a truism that extends to microplastics.